| Cari Amici, Un anno fa è venuto a mancare uno dei miei amici di lunga data, CARMINE TRUBIANO. Il suo profilo ed il suo stile di vita potevano essere associabili a quelli di un antico romano! Un uomo come lui è insostituibile – si può solo ricordare e rimpiangere. Il seguente è l’elogio funebre che ebbi il grande onore di fare al suo funerale. Non sto qui a dirvi che persona meravigliosa fosse Carmine. Se non lo aveste già conosciuto e non ne aveste un’opinione positiva, voi non sareste qui in questo momento. E sono così felice che voi lo abbiate conosciuto, perché in caso contrario, come potrei mai descrivervelo? In tutta la mia vita, io non posso pensare a nessuno che fosse come lui. E ciò rende questo elogio così difficile. Non c’è nessuno che lo possa sostituire. Non c’è modo di esprimere chi fosse con un elogio funebre di cinque minuti. Quindi ho intenzione di condividere solo qualche ricordo personale. Ho conosciuto Carmine quasi 25 anni fa, quando gestiva il ristorante da Filippo, che frequentavo spesso. Siamo diventati subito amici. Lo chiamavo “fratellino” e lui mi chiamava “fratellone”. Questo era molto buffo, sia per l’età sia per la nostra fisicità, sebbene per il secondo, come vedete, lo sto raggiungendo velocemente. Vi devo dire che era un evento, a quei tempi, visitare lui e la sua cara, indimenticabile mamma. Allora io vivevo a Revere e non guidavo. E anche se avessi guidato, ciò accadde prima che costruissero la galleria Ted Williams. Quindi visitare il 50 di Washington Ave., con il treno o con la macchina, era comunque un viaggio. Una volta mi presentai senza invito. Non aveva proprio idea che io stessi arrivando. Senza nessuna sorpresa mi disse: “Uhè, Fratellone.” In 60 secondi ero seduto a tavola e mi mise del cibo davanti. Dal frigo tirò fuori degli hamburger, non di carne bovino, ma di cervo che cacciò lui stesso con il suo amico Luigi Andreassi. Mentre mangiavo mise a bollire l’acqua per la pasta. Poi andò alla credenza e tirò fuori una scatola di pelati. E mentre si cuoceva il sugo, prese dal frigo un tartufo, dal quale tagliò una scaglia per metterla nella salsa. Quando il sugo fu quasi pronto, andò al freezer e tirò fuori una busta di maltagliati fatti in casa. Così continuò la cena. In seguito, quando mi trasferì a Natick, distavamo solo 5 minuti in macchina. Quindi quando mi chiamava e mi invitava per finire gli “avanzi”, immaginate quanto velocemente guidavo per giungere? Una cosa che mi rimase impressa di Carmine è che non giudicava moralmente le persone. Lasciava che le persone si esprimessero liberamente. Con un’importante eccezione. Non accettava alcun tipo di snobismo o di arroganza. Odiava gli snobs a tal punto che qualche volta penso che minimizzasse la sua istruzione e cultura e faceva volutamente la parte del bifolco. Così facendo, gli snobs lo avrebbero respinto e lui poteva trascorrere il suo tempo con le persone che gli andavano a genio. Con me non ci fu presunzione e parlammo per ore di letteratura, arte e cultura italiana. E riusciva veramente a leggere e scrivere in latino. C’era un motivo per il quale odiava lo snobismo ed è molto importante che ve lo racconti. Quando lavoravo al centro commerciale vedevo queste casalinghe ricche e annoiate comprare allegramente la padella in ghisa suggerita dal loro istruttore di cucina. Beh, gli italiani usavano quelle padelle 150 anni fa. Fermatevi a pensare per un momento che i contadini a quei tempi, che non sapevano né leggere né scrivere, una volta all’anno uccidevano un maiale e poi ne ricavavano la pancetta, il guanciale e le salsicce, e sapevano preservare tutto alla perfezione in modo che la famiglia lo potesse mangiare tutto l’anno. Potevi andare alla scuola di medicina di Harvard per 25 anni e non imparare a fare tutto ciò. Carmine ebbe una grande curiosità intellettuale. Se non l’avesse avuta non avrebbe studiato a Roma e in Francia e non si sarebbe né laureato né avrebbe ottenuto il master a Middlebury College. Allo stesso tempo conobbe benissimo la vera cultura. Ecco perché, senza troppi problemi, Carmine insegnò a noi amici certe tradizioni che anche in Italia stanno scomparendo. Questo era un altro aspetto di Carmine che non tutti capivano. Se anche in Italia le persone vanno al negozio a comprare le salsicce, perché si doveva prendere la briga di invitare i suoi amici per fare le salsicce? Ma è esattamente ciò che accadde un giorno 15 anni fa. Eravamo in cinque: Carmine, suo cugino Cesidio dall’Italia, suo cugino Carmine dal Canada, Tony Onorato ed io. Eravamo lì, nella cantina del 50 Washington Ave. e sul tavolo c’erano 30 kg di macinato di maiale. “Di solito ne faccio solo 25 kg,” ci spiegò Carmine. Lavò ogni involucro a mano e misurò con attenzione il pepe. E facemmo 30 kg di salsicce, la nostra fatica venne ricompensata dai litri di vino rosso fatto in casa da Luigi. Non ci ubriacammo, ma comunque bevemmo molto quel giorno. Dirò solo che se una zanzara ci avesse punto avrebbe avuto bisogno di un bicchiere d’acqua come chaser (da bere dopo un superalcolico). Alla fine della festa, ero seduto, inconsapevole del fatto che Carmine fuori avesse acceso il grill. Senza dire una sillaba, mi diede un piatto con un hamburger fatto di carne di salsiccia avanzato. Per questa ragione questo momento mi fa tornare alla memoria un ricordo di incredibile generosità e la mancanza di presunzione con cui diede da mangiare a chi lo circondava. Per lui era normale preparare una lasagna senza glutine e portarne un pezzo al suo fisioterapista. Oppure quella volta che stavamo parlando al telefono in merito a delle ricette a base di coniglio. Il giorno successivo bussò alla mia porta. Aveva in mano due recipienti, uno con il coniglio a “cif e ciaf” e uno con il coniglio “in umido”. Non c’è tempo per raccontare tutte queste storie. Comunque, non posso esimermi dal raccontare una mia festa di compleanno di vent’anni fa. Carmine venne a Revere e mi portò una lasagna e una porchetta intera. Abbastanza per sfamare tutta la famiglia e i miei amici. Lui faceva delle cose così. E adesso che ci penso, in 25 anni lui non mi ha chiesto mai un favore. Lui faceva tanti favori agli altri, ma non ne chiedeva nessuno. Nel corso della sua intera vita Carmine amava scrivere poesie. Durante la sua malattia, mentre era ricoverato alla clinica Eliot qui a Natick, egli scrisse diverse poesie. Potevano essere state scritte da qualcuno nato non nel 1936 ma nel 1886. Una di queste la finì in latino! Tra queste poesie, ce n’era una che mi è rimasta particolarmente impressa. Inizia così:

Eccomi all’orlo del profondo abisso

Che separa la morte dalla vita

Di vivere la spem quasi è finita

Solo mi sento come il crocifisso

Come lui di morir non ho paura

Perché male a nessuno ho fatto mai

Forse una volta o due anch’io sbagliai

ma l’alma mia rimase sempre pura

Del futuro non vedo alcun bagliore

Le tenebre mi dicon “Non sperare

fugge dai cimiteri anche la speme.”

Dentro di me qualcosa assai mi preme

Mi sento forte ancora da lottare

Pur se lottar vuol dire grande dolore Due settimane prima che egli morisse, io ero su Facebook, sul profilo di Linda Onorato vi era una foto di un cena meravigliosa. Sapendo quanto era debole Carmine, ho immaginato che la foto fosse di qualche anno prima. Ella rispose, “No, è adesso. Vieni!” Erano le 9.39 di sera e dieci minuti dopo ero a casa di Carmine. Seduti al tavolo c’erano Linda Onorato, Kristin Brothers e Linda Zaleski. Eccolo lì il vecchio leone, ammaliatore, che leggeva le sue romantiche poesie a queste tre donne sensibili, visibilmente emozionate, tanto da avere le lacrime che le rigavano i volti. Quando le tre signore andarono via, io rimasi altri 45 minuti a parlare con Carmine. La nostra ultima conversazione. Era molto stanco, era stato il suo ultimo Convivio. “Prendi un altro poco di vino. Prendi un poco di Centerba. Vorresti del limoncello?” Gli dissi” Carmine, sei stato un amico meraviglioso per tutti noi e in tutti questi anni non ci hai mai chiesto nulla in cambio. Noi in cambio siamo stati dei buoni amici?” Egli replicò “Certo, non voglio nulla in cambio. Ciò che conta è l’affetto”. *** A seguire il suo necrologio (scritto da me). Carmine A. Trubiano, 80 anni, di Natick, morto in pace il 27 luglio 2016 all’ospedale di Brigham & Women’s. Gli fu recentemente diagnosticato una forma di leucemia mieloide acuta. Il sig. Trubiano nacque a Castiglione a Casauria, un paese di 850 abitanti nella provincia italiana di Pescara, il primogenito di Ivra (Ranella) Trubiano and Lucio Trubiano. Egli frequentò il Liceo Classico Ovidio vicino Sulmona,dove studiò lingua e letteratura latina e anche il greco classico. Dopo ultiriori studi a Roma, vise in Francia per tre anni dove imparò a fare il saldatore e la cucina francese. Lavorò in Olanda per sette mesi prima di emigrare negli Stati Uniti nell’ottobre del 1960. (divenne cittadino americano nel maggio del 1966.) Dal 1960 al 1963 lavorò per la Westinghouse Electric a Boston, mentre studiava inglese alla scuola serale di Wellesley. Dal 1964 al 1973 fu socio di un impresa metallurgica a Framingham. Egli ricevette la B. A. in francese all’Università di Boston (1973), un M. A. in Didattica e italiano nella stessa università (1975), e completò un corso di lavoro per D.M.L. in italiano al Middlebury College (1978). Dopo un breve incarico come insegnante di italiano presso la Watertown High School (1975), egli insegnò lingua e letteratura italiana alla Newton North High School dal 1975 al 1981. Diresse alcune sceneggiature a Newton e Middlebury, incluso “La giara,” di Pirandello, “L’uva,”di Tozzi, “Il dentista e la dentista di Fratti”, “La favola del figlio cambiato,”di Pirandello e la sua“L’apologia di Don Venanzio.” Negli anni 1980 e ‘90, il Sig. Trubiano era un personaggio molto noto a Boston, dove lavorò come manager per diversi ristoranti importanti, tra i più famosi il Ristorante di Filippo. Egli fu anche membro dell’associazione di lingue straniere del Massachusetts, il Club di educazione italo-americano (Wellesley), e la società di Dante Alighieri (Cambridge). Il Sig. Trubiano fu un prolifico poeta che continuò a scrivere fino alla sua morte. Le sue poesie sono racchiuse in due raccolte, “America amara” (115 poesie) e “A Najwa” (38 poesie). Al Sig. Trubiano sopravvivono tre figli, Luciano, Enzo e Mario; la sorella Pasquina Gaspari dell’Italia, i fratelli Reno Trubiano di Framingham, Mario Trubiano di Rhode Island, Dino Trubiano e Fausto Trubiano di Natick. La funzione funebre si terrà sabato 10 all’una nella cappella di John Everett & Sons, 4 Park Street a Natick Common. Non fiori, ma donazioni da fare al Natick Visiting Nurse Association (www.natickvna.org) oppure Bay Path Elder Services (www.baypath.org). |

Dear friends, A year ago today, I lost one of my dearest friends of my entire life, CARMINE TRUBIANO. His profile could have been on an Ancient Roman coin – and his life-style bore some similarities, as well! A man such as him you don't replace – you remember, and you mourn. The following is the eulogy that I had the great honor of giving at his funeral. I'm not going to stand here and tell you what a wonderful person Carmine was. If you didn't already know him and think that, you wouldn't be here right now. And I'm so happy that you did know him, because if you didn't, if you had never met him, how can I possibly begin to describe him? In my whole life, I can't think of anyone who was like him. And that is what makes this so hard. There's no one to replace him with.

There's

no way to express who he was in a five-minute eulogy. So I'm going to

share only a couple of personal memories.

I

first met Carmine almost 25 years ago, when he was the manager at

Filippo's Restaurant, which I used to visit frequently. We became

fast friends. I called him “fratellino”, which means little

brother, and he called me “fratellone”, which means big brother.

This was very comical, both in terms of our ages and our sizes –

although regarding the latter, as you can see I am catching up fast.

I have

to tell you what an event it was, in those days, to visit him and his

dear, unforgettable mother. At the time I was living in Revere, and I

didn't drive. Even if I did drive, this was before the days of the

Ted Williams Tunnel. So to visit 50 Washington Ave., either by train

or by car, was something of a journey. Once, I showed up uninvited.

Absolutely uninvited – he had no idea I was coming. With no

surprise in his voice at all, he said, “Uhé, fratellone.”

Within 60 seconds, I was seated at the table and there was food in

front of me. From the fridge he pulls out a dish of hamburgers, made

not from beef but from the meat of a deer that he himself had shot

with Luigi Andreassi. While I'm eating that, he starts boiling some

water for the pasta. Then he goes to the cupboard and pulls out a

can of tomatoes. And as the sauce is cooking he goes to his freezer

and pulls out a whole truffle, from which he shaves one tiny sliver

into the sauce. And when the sauce is almost done, he goes to his

freezer and pulls out a bag of homemade triangular maltagliati. And

so the meal went. Later, when I moved in Natick, suddenly the long

journey was only a five-minute car ride. And when he would call me

and invite me over for quote-unquote “leftovers,” can you imagine

how fast I drove over there?

One

thing that struck me about Carmine was that he was utterly

unjudgmental. He let people be whoever they were going to be. With

one notable exception. He could not abide any sort of snobbery or

pretension. He hated snobs so much that sometimes I think he

downplayed his own education and culture and played the part of the

peasant. This way, the snobs would be repelled, and then he could

hang out with the people that he actually liked. With me, there was

no pretension, and we had many long conversations about literature

and art and every aspect of Italian culture. And by the way, he

really could read and write Latin.

But

there was a reason why he hated snobbery, and it's very important

that I tell you. When I used to work at the mall, I used to see these

rich, bored housewives come in and giddily buy a cast-iron pan that

was recommended by their cooking instructor. Well, the Italians were

using those pans 150 years ago. And stop to think for a moment that

the peasants of those times, who couldn't even read or write, would

once a year kill a pig, and with that pig would make the pancetta and

the guanciale and the sausages, and they knew how to preserve

everything perfectly, without any of the meat going bad, and the

family would eat this meat for a whole year. You could go to Harvard

Medical School for 25 years and not learn how to do all of that.

Carmine did have a great intellectual curiosity. If he didn’t he

wouldn’t have studied in Rome and France and gotten his Bachelors

and Masters at BU and studied for his doctorate at Middlebury

College. At the same time, he knew full well what real culture was.

This

is why, without making a big deal of it, Carmine would teach us

friends certain traditions that even in Italy are disappearing. This

was another aspect of Carmine that not many people understood. If

even in Italy people go to the store to buy sausages, why would he go

through the trouble of inviting friends over for a sausage-making

party? But this is exactly what occurred one unforgettable day about

15 years ago. There were five of us: Carmine, his cousin Cesidio

from Italy, his cousin Carmine from Canada, Tony Onorato, and myself.

There we were, in the basement of 50 Washington Ave., and on the

table before us was 60 pounds of ground pork. “I usually make only

50 pounds,” Carmine explained. And he washed each casing by hand.

And he measured the ground pepper carefully. And we made 60 pounds

of sausages, our toil alleviated by gallons of Luigi’s homemade red

wine. I won’t say that we imbibed too much that day. Then again,

I won’t say that we didn’t imbibe too much that day. I’ll say

only that if a mosquito bit any one of us that day, it would have

needed a glass of water as a chaser.

At the

end of the party, I was sitting on a chair, unaware of the fact that

outside Carmine had lit the charcoal grill. Without saying a

syllable, he handed me a dish with a grilled patty made from the

leftover sausage meat, in a grilled bun. For whatever reason,

remembering that moment reminds me of his incredible generosity and

the lack of pretention with which he fed everyone around him. For

him it was a normal thing to do to make a gluten-free lasagne and

bring a piece of it to his physical therapist. Or the time that we

were talking on the phone and I asked him about rabbit recipes. The

very next day there’s a knock on my door. There he is, holding two

plastic containers, one with rabbit “cif e ciaf” and the other

with rabbit “in umido.”

There just isn’t time to tell you all these stories. However, I would be remiss not to mention a birthday party of mine, about 20 years ago. Carmine drove to Revere and brought an entire lasagne and an entire porchetta. Enough to feed my entire family and friends. He did things like that. And come to think of it, in 25 years he never asked me a favor. He did a lot of favors, but he never asked for one.

Throughout

his life Carmine loved to write poetry. During his final illness,

while at the Eliot rehab here in Natick, he wrote several poems.

They could have been written by someone born not in 1936 but 1886.

One of them ended in Latin! Of these poems, there was one that

struck me in particular. It begins “Here I am at the edge of the

deep abyss that separates death from life.”

Eccomi

all’orlo del profondo abisso

Che

separa la morte dalla vita

Di

vivere la spem quasi è finita

Solo

mi sento come il crocifisso

Come

lui di morir non ho paura

Perché

male a nessuno ho fatto mai

Forse

una volta o due anch’io sbagliai

ma

l’alma mia rimase sempre pura

Del

futuro non vedo alcun bagliore

Le

tenebre mi dicon “Non sperare

fugge

dai cimiteri anche la speme.”

Dentro

di me qualcosa assai mi preme

Mi

sento forte ancora da lottare

Pur

se lottar vuol dire grande dolore

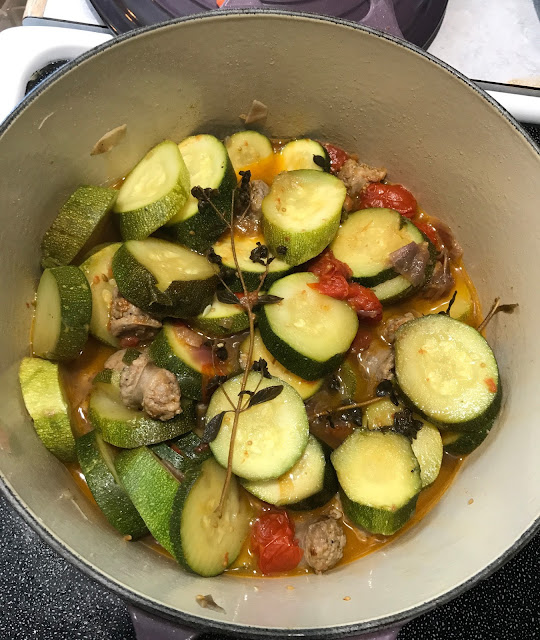

Less

that two weeks before he died, I was on Facebook, and on Linda

Onorato’s timeline there was a photo of a wonderful meal. Knowing

how weak Carmine was, I figured it was from several years ago. She

replied, “No, this is happening right now. Come over.” This was

at 9:39 p.m. At 9:51 I was in Carmine’s driveway. Seated at the

table were Linda Onorato, Kristin Brothers, and Linda Zaleski. There

was the old lion, the charmer, reading his romantic poetry to these

three blushing women, tears trickling down their cheeks.

The

three ladies left. I remained for about 45 more minutes, until about

11:40. Just me and Carmine, talking. Our final conversation.

He was

very tired, yet still he was the host of the Bacchanal. “Have some

more wine. Have some more Centerba. Would you like some limoncello?”

I said

to him, “Carmine, you’ve been such a wonderful friend to all of

us, and in all these years you’ve never asked anything of us. Have

we been good friends to you in return?”

He

replied, “Of course. I don’t want anything in return. All that

matters is the love.”

*** The following was his obituary (which I also wrote).

Carmine A.

Trubiano, age 80, of Natick, died peacefully on July 27, 2016 at

Brigham & Women’s Hospital. He had recently been diagnosed

with acute myeloid leukemia.

Mr. Trubiano was

born in Castiglione a Casauria, a town of 850 inhabitants in the

Italian province of Pescara, the eldest child of Ivra (Ranella)

Trubiano and Lucio Trubiano. He attended the Liceo Classico Ovidio

in nearby Sulmona, where he studied Latin Language and Literature, as

well as Classical Greek. After further studies in Rome, he lived in

France for three years, where he learned both welding and French

cuisine. He worked in Holland for seven months before emigrating to

the United States in October, 1960. (He would become an American

citizen in May, 1966.) From 1960 to 1963 he worked for Westinghouse

Electric in Boston, while studying English at Wellesley High Night

School. From 1964 to 1973 he co-owned a welding business in

Framingham. He received a B. A. in French at Boston University

(1973), an M. A. in Education and Italian at Boston University

(1975), and completed coursework for a D.M.L. in Italian at

Middlebury College (1978). After a brief tenure teaching Italian at

Watertown High School (1975), he taught Italian Language and

Literature at Newton North High School from 1975 to 1981. In Newton

and Middlebury he directed several plays, including Pirandello’s

“La giara,” Tozzi’s “L’uva,” Fratti’s “Il dentista e

la dentista,” Pirandello’s “La favola del figlio cambiato,”

and his own “L’apologia di Don Venanzio.”

In the 1980s and

‘90s, Mr. Trubiano was a well-known figure in the North End of

Boston, where he worked as a manager for several important

restaurants, most notably Ristorante Filippo. He was also a member

of the Massachusetts Foreign Language Association, the

Italian-American Educational Club (Wellesley), and the Dante

Alighieri Society (Cambridge).

Mr. Trubiano was a

prolific poet who continued to write poems right up to his death.

His poetry includes two collections, “America amara” (115 poems)

and “A Najwa” (38 poems).

Mr. Trubiano is

survived by three sons, Luciano, Enzo, and Mario; and siblings,

Pasquina Gaspari of Italy, Reno Trubiano of Framingham, Mario

Trubiano of Rhode Island, Dino Trubiano of Natick, and Fausto

Trubiano of Natick.

A memorial service

will be held on Saturday, September 10th at 1 p.m. in the chapel of

the John Everett & Sons Funeral Home, 4 Park Street at Natick

Common. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to the Natick

Visiting Nurse Association (www.natickvna.org) or Bay Path Elder

Services (www.baypath.org).

|

| N.B. La precedente traduzione italiana è del sig. Antonio Buccilli (Pescara), della mia versione originale in inglese. Un sentito ringraziamento al sig. Buccilli, e al suo figlio Cesidio Buccilli per la sua facilitazione. – L.C. |