| Raramente pubblico ricette per i dolci. Non ho una golosità di dolci. Anche il caffè prendo amaro. Tuttavia, mia bella moglie Jeanette mi ha fatto questi, sapendo che il sapore di limone e la leggerezza mi piacerebbero tanto. (Notate che la ricetta non richiede uova.) Questi biscotti semplici ma saporiti farebbero un finale perfetto per un pasto italiano di stile casereccio. Ingredienti 60 g zucchero a velo 170 g (1½ panetti) burro ½ cucchiaino sale (preferibilmente extra-fine) 2 cucchiaini estratto di limone 65 g amido di mais 130 g farina multiuso, non sbiancata Preparazione Preriscaldate il forno a 150º C. Preparate due teglie per biscotti, o ungendole leggermente, o foderandole con carta pergamena. (Invece di pergamena, Jeanette usa i tappetini in gomma siliconica.) In una ciotola di medie dimensioni, mescolate lo zucchero, il burro, il sale, ed estratto finché cremosi. Aggiungete l’amido e la farina. Mescolate l’impasto finché coeso. Con un cucchiaio, fate cadere l’impasto sulle teglie unte. Fateli cuocere per 25 minuti, o finché leggermente dorati. Togliete le teglie dal forno. Fate rimanere i biscotti sulle teglie per 5 minuti. Poi rimuoveteli e disponeteli su una griglia per raffreddare. |

I rarely post recipes for sweets. I do not have a sweet tooth. Even my espresso I drink black. However, my beautiful wife Jeanette made me these, knowing that I would love their lemon flavor and their lightness. (Note that the recipe doesn't call for eggs.) These simple but flavorful cookies would make a perfect finale to a homestyle Italian meal. Ingredients ½ C (2 oz.) confectioners' sugar ¾ C (1½ sticks, 6 oz.) butter ½ tsp salt (preferably extra-fine) 2 tsp lemon extract ½ C (2 oz.) cornstarch 1 C (4¼ oz.) unbleached all-purpose flour Preparation Preheat oven to 300º F. Prepare two baking pans, either by greasing them lightly, or by lining them with parchment paper. (Instead of parchment, Jeanette uses baking pads made of silicone rubber.) In a medium-sized bowl, mix the sugar, butter, salt, and extract until creamy. Add the cornstarch and flour. Stir until the dough is cohesive. With a tablespoon, drop the dough onto the greased baking sheets. Bake for 25 minutes, or until lightly golden brown. Remove the baking sheets from the oven. Let the cookies remain on the sheets for 5 minutes. Then remove them and place them on a rack to cool. |

Diario dell’Esperienza Italoamericana

A Journal of the Italian-American Experience

sabato 31 agosto 2013

Soffi di limone / Lemon puffs

martedì 27 agosto 2013

Su l'ali del canto / On wings of song

| SU L’ALI DEL CANTO

Testo originale tedesco di Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) Traduzione italiana di Giosuè Carducci (1835-1907) Lungi, lungi su l’ali del canto Di qui lungi recare io ti vo’: Là, nei campi fioriti del santo Gange, un luogo bellissimo io so. Ivi rosso un giardino risplende Della luna nel cheto chiaror: Ivi il fiore del loto ti attende, O soave sorella dei fior. Le vïole bisbiglian vezzose, Guardan gli astri su alto passar; E fra loro si chinan le rose Odorose novelle a contar. Salta e vien la gazzella, l’umano Occhio volge, si ferma a sentir: Cupa s’ode lontano lontano L’onda sacra del Gange fluir. Oh che sensi d’amore e di calma Beveremo nell’aure colà! Sogneremo, seduti a una palma, Lunghi sogni di felicità. |

ON WINGS OF SONG Original German text by Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) English translation (of the Italian) by Leonardo Ciampa Far, far away, on wings of song Far from here I’m going to go: There, in the flowery fields of the blessed Ganges, to a very beautiful place I know. There a red garden shines In the quiet light of the moon: There the lotus flower awaits you, O sweet sister of the flowers. The charming violets whisper, They watch the stars pass above; And among them the roses bend down, Fragrant tales to recount. The gazelle jumps and approaches, the human eye turns, stops to listen: faintly one hears, far far away, the sacred wave of the Ganges flow. Oh what feelings of love and of calm We will imbibe from the breezes over there! We will dream, seated under a palm tree, Long dreams of happiness. English translation Copyright © Leonardo A. Ciampa |

E adesso, la stessa poesia musicata da Leonardo Ciampa, cantata dai MetroWest Choral Artists,

sotto la direzione del compositore (18 aprile 2012).

And now, the same poem set to music by Leonardo Ciampa, sung by the MetroWest Choral Artists,

under the direction of the composer (18 April 2012).

|  |

Braciole, Southern Italian style beef roulades

On Sundays, my grandmother made a big tomato sauce, a.k.a. sugo. And in every sugo she put meatballs, a rack of pork ribs, and a big hunk of sirloin. Sometimes she also put sausages.

The Christmas sugo and the Easter sugo followed the same recipe as every Sunday, with only one difference: the addition of the braciole.

I couldn't understand why so many recipes for Neapolitan braciole were almost identical to that of my Sicilian grandmother. I did a little research. I discovered that the invention of braciole is attributed to the Cavalier Signor Ippolito Cavalcanti, Duca di Buonvicino. The Duke was the author of a very important cookbook, Cucina Teorico-Pratica. And the moment that I saw the year of the book's publication — 1837 — I immediately understood. It falls neatly within the years of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1816-1861), when southern Italy was under Bourbon, therefore French, rule.

That very era spawned the cuisine of the monsù. The word “monsù” (also written “monzù”) is a corruption of monsieur. It refers to the chefs of this era, like the good Duke, who were influenced by French cuisine. And many recipes of the monsù were very similar in the Kingdom of the Naples and the Kingdom of Sicily. (A very good example is the sartù di riso, a type of timballo only with rice instead of pasta.)

Who knew that this recipe by my humble grandparents was such a noble dish!

My grandmother was a creature of habit. She rarely experimented or improvised in the kitchen; she repeated the same recipes and procedures every year. Braciole were no exception. She always used thin steaks from the top round. (Even though they're thin, you still have to beat them with a meat pounder and wax paper.)

My grandmother's fillings were always the same:

|

| The steaks, before pounding. |

My grandmother's fillings were always the same:

- slices of prosciutto or ham

- slices of salame or soppressata

- slices of mild provolone

- fresh parsley

- freshly grated pecorino (My grandmother never used parmigiano. Parmesan was not part of the cuisine of the Southern Italian farmers of the olden days.)

- hard-boiled eggs

- raisins (Certain recipes say to soak them in water first.)

- pine nuts (I prefer pistachios, which are less expensive, more delicious, and more Sicilian! Even though ours are from California, they are excellent. You could halve them if you want; all you need is 6 or 12 of them.)

- some homemade breadcrumbs (not shown)*

one oil-cured black olive (In my grandmother's fridge, she always had a jar of these wrinkly olives. She would put one of them in certain dishes, e.g., her pizza (Sicilian-style, with a thick crust), or her "spinach pizza" which was actually a calzone of spinach, ground beef, and a few cold cuts for flavor. I would say to experiment with other olives; either kalamata or the big green Sicilian olives would be perfect. But I say this hesistantly, for these oil-cured olives were for my grandmother something of a trademark.)

one oil-cured black olive (In my grandmother's fridge, she always had a jar of these wrinkly olives. She would put one of them in certain dishes, e.g., her pizza (Sicilian-style, with a thick crust), or her "spinach pizza" which was actually a calzone of spinach, ground beef, and a few cold cuts for flavor. I would say to experiment with other olives; either kalamata or the big green Sicilian olives would be perfect. But I say this hesistantly, for these oil-cured olives were for my grandmother something of a trademark.)

* = Addendum (September 2016): Last month I was going through a file of old, yellowed recipes. I found a slip of paper on which I'd taken down my grandmother's recipe for braciole. I had no recollection that she and I ever discussed it. True to form, there was more detail about how to fasten the braciole than there was about how to cook them! (She was a seamstress!) Fortunately, in this blog post (which I wrote from memory), I remembered everything, except for one single ingredient: she added a little bit of breadcrumbs. Certainly a Sicilian touch. However, if you add them, be sure to dampen them a little with oil, milk, water … or a drop of wine!

Here I will confess that sometimes I found my grandmother's braciole a little dry. I saw a recipe that suggests to spread a little lard or olive oil on the meat. I got the idea to make a paste. I often have homemade lard in my fridge, but today I didn't. And in the garden I didn't have much parsley, but I had a good amount of thyme. Thyme being a wonderful complement to beef, I chose that. Therefore, in the food processor I put olive oil, thyme, pecorino, black pepper, and I added a garlic clove. A paste like this does wonders in many types of roulades.

However, here I made a little mistake. I decided to add also the pistachios to the food processor. The paste was fantastic and very interesting. But at the end, when I ate the finished braciole, I couldn't sink my teeth into the pistachios, which make an important contrast to the sweet raisins.

So, how do we bind the braciole? In my memory, my grandmother used only steel pins. However, my mother says that before, my grandmother used to use kitchen string. I don't know why she changed methods.

The next step is to brown the braciole. In her biggest frying pan, my grandmother put olive oil, sliced onion, salt, and pepper. (You wouldn't put garlic if there is already some in the braciole.) In this pan, she browned, in turn, not only the braciole, but all the meats that were going into the sugo. The big hunk of sirloin ... the rack of pork ribs ... the sausages if she was using them (but sometimes she put them raw into the sugo) .... and the famous meatballs ...

Now, how do we deglaze this pan, which now contains all the flavors of Heaven?

My grandmother never put either wine or broth in her sugo. To deglaze this pan, she put one 6-oz. can of tomato paste and two can's-full of water. This tasty sughetto ("little sauce") went into the big pot which already contained the rest of the sugo.

My grandmother never put either wine or broth in her sugo. To deglaze this pan, she put one 6-oz. can of tomato paste and two can's-full of water. This tasty sughetto ("little sauce") went into the big pot which already contained the rest of the sugo.

(A short digression on meatballs. To put garlic, or not to put garlic? If we put raw garlic, it's too strong. If we don't put any garlic, a little something is missing. What did my grandparents do? Many a time did I witness this procedure. They kept their slices of stale bread in the cold oven. After a couple of days they got very hard. My grandfather took a garlic clove in his fingers and physically scraped it into the hard bread. Then, he put this very fragrant bread into the hand-held grater

— the type that they use today for parmesan, except that in those days the graters were all steel. This is how they made homemade breadcrumbs that then went into the meatballs. Just imagine the aroma!)

(A short digression on meatballs. To put garlic, or not to put garlic? If we put raw garlic, it's too strong. If we don't put any garlic, a little something is missing. What did my grandparents do? Many a time did I witness this procedure. They kept their slices of stale bread in the cold oven. After a couple of days they got very hard. My grandfather took a garlic clove in his fingers and physically scraped it into the hard bread. Then, he put this very fragrant bread into the hand-held grater

— the type that they use today for parmesan, except that in those days the graters were all steel. This is how they made homemade breadcrumbs that then went into the meatballs. Just imagine the aroma!)

In total, Grandma's sugo cooked for several hours. The already-browned meatballs went in only 30 minutes before the end. The other meats each had their own cooking time. The braciole she put in an hour before the end. (And by the way, she put in the basil only 5 minutes before the end!)

At this point, I must stray from Grandma's kitchen, for she never made braciole separate from the big sugo.

You will definitely have opportunity to make only the braciole, without a big sugo. In fact, the original, 19th-century braciole were like that, with their own sughetto.

You will definitely have opportunity to make only the braciole, without a big sugo. In fact, the original, 19th-century braciole were like that, with their own sughetto.

After browning the braciole, deglaze the pan. I used just water. Red wine would be delicious, especially if you use Nero d'Avola or Lacryma Christi del Vesuvio. For goodness sake, please don't use Chianti or another wine that clashes with Southern Italian food. (Ironically, two wines of the extreme North concord beautifully with a red sauce: the bold Barbera and the docile Dolcetta d'Alba.)

If you don't use wine, you could use homemade beef or pork stock. But water works perfectly well. And the braciole already contain a complex array of flavors. Don't hesitate to use simple water, like I used.

If you don't use wine, you could use homemade beef or pork stock. But water works perfectly well. And the braciole already contain a complex array of flavors. Don't hesitate to use simple water, like I used.

Into the deglazed pan, put peeled tomatoes that you've already puréed in the blender. (Don't use canned tomato purée or tomato paste.) Add a little salt and pepper, but never add sugar to a sugo. Grandma used raisins and a piece of carrot. You would do well to add a third ingredient: a few sun-dried tomatoes. (I never saw them in my grandmother's kitchen, but she spoke nostalgically about sun-dried tomatoes, which figured prominently in her mother's cooking. It's not like they could afford much meat! That was one advantage of marrying my grandfather, a butcher!)

Cook the sughetto slowly for one hour. During the cooking, you can add a little water as necessary. But you never add wine or broth after the initial deglazing. You don't want to overwhelm the flavor of the tomatoes.

I never took the braciole out of the pan, even during the deglazing; I cooked them a half hour per side. If you want to cook them less, you can brown the braciole, take them out of the pan, deglaze the pan, cook the sughetto for 30 minutes, then put the braciole back into the pan and cook them 15 minutes per side. The total cooking time in still 60 minutes.

Like other recipes of the monsù (e.g., Agglassato), this sughetto makes for a phenomenal sauce to put on pasta. This way, you can make the first course and second course simultaneously. That's just what I did, choosing campanelle as the pasta. In my opinion, campanelle are the perfect pasta for this sughetto; I can't give you a logical reason why.

This recipe first appeared as part of "Our Grandmother's Recipes."

Labels:

Beef,

Bourbonic recipes,

Cucina napoletana,

Cucina siciliana,

Manzo,

Monsù,

Monzù,

Neapolitan cuisine,

Ricette borboniche,

Second Courses,

Secondi,

Sicilian cuisine,

Signature dishes

Braciole di manzo, di stile meridionale

La domenica, Nonna faceva il sugo. E in ogni sugo metteva le polpette, il carré delle costole di maiale, e un grosso pezzo di controfiletto. Qualche volta metteva pure le salsicce.

Il sugo natalizio e il sugo pasquale seguivano la stessa ricetta di ogni domenica, con una sola differenza: l’aggiunta delle braciole.

Non potevo capire perché tante ricette per le braciole napoletane erano quasi identiche a quella di mia nonna siciliana. Ne ho fatto un po’ di ricerca. E ho scoperto che l’invenzione delle braciole si attribuisca al Cav. Sig. Ippolito Cavalcanti, Duca di Buonvicino. Il Duca fu l’autore di un libro culinario importantissimo, Cucina Teorico-Pratica. E il momento che ho visto l’anno di pubblicazione di questo volume — 1837 — ho capito subito. Cade nettamente dentro gli anni del Regno delle Due Sicilie (1816-1861), quando l’Italia meridionale era sotto il dominio borbone, quindi francese.

Questa stessa epoca generò la cucina dei monsù. La parola “monsù” (scritta anche “monzù”) è una deformazione di monsieur. Si riferisce ai cuochi di quest’epoca, come il buon Duca, ch’erano influenzati dalla cucina francese. E molte ricette dei monsù erano similissime nel Regno di Napoli e nel Regno di Sicilia. (Un buonissimo esempio è il sartù di riso.)

Chi sapeva che questa preparazione dei miei nonni campagnoli fosse un piatto così nobile!

Non potevo capire perché tante ricette per le braciole napoletane erano quasi identiche a quella di mia nonna siciliana. Ne ho fatto un po’ di ricerca. E ho scoperto che l’invenzione delle braciole si attribuisca al Cav. Sig. Ippolito Cavalcanti, Duca di Buonvicino. Il Duca fu l’autore di un libro culinario importantissimo, Cucina Teorico-Pratica. E il momento che ho visto l’anno di pubblicazione di questo volume — 1837 — ho capito subito. Cade nettamente dentro gli anni del Regno delle Due Sicilie (1816-1861), quando l’Italia meridionale era sotto il dominio borbone, quindi francese.

Questa stessa epoca generò la cucina dei monsù. La parola “monsù” (scritta anche “monzù”) è una deformazione di monsieur. Si riferisce ai cuochi di quest’epoca, come il buon Duca, ch’erano influenzati dalla cucina francese. E molte ricette dei monsù erano similissime nel Regno di Napoli e nel Regno di Sicilia. (Un buonissimo esempio è il sartù di riso.)

Chi sapeva che questa preparazione dei miei nonni campagnoli fosse un piatto così nobile!

Nonna era una persona abitudinaria. Raramente esperimentava o improvvisava nella cucina; ripeteva le stesse ricette e procedure ogni anno. Le braciole non ne facevano eccezione. Nonna usava sempre bistecche sottili del controgirello. (Anche se siano sottili, si devono battere col batticarne e la carta cerata.)

Poi, il ripieno di Nonna era sempre:

|

| Le bistecche prima d’esser battute. |

Poi, il ripieno di Nonna era sempre:

- fette di prosciutto (o prosciutto cotto)

- fette di salame o soppressata

- fette di provolone dolce

- prezzemolo fresco

- pecorino grattugiato (Nonna non usava mai il parmigiano. Il parmigiano non faceva parte della cucina degli agricoltori meridionali di una volta.)

- uova sode

- uvette (Certe ricette dicono di farle ammorbidire in anticipo in acqua.)

- pinoli (Io preferisco i pistacchi, che sono meno cari, più deliziosi, e più siciliani! Anche se i nostri siano californiani, sono eccellenti. Li potreste dimezzare se vogliate; ve ne servono solo 6 o 12.)

- del pangrattato (non figura nelle foto)*

un’oliva nera conservata sott’olio (In frigo, Nonna aveva sempre un barattolo di queste olive spiegazzate. Ne metterebbe una in certi piatti, e.g., la pizza, o la calzone di spinaci e manzo macinato. Io direi di provare altre olive; le kalamata e le grandi olive verdi siciliane sarebbero perfette. Ma dico questo con esitazione, poiché quest’oliva nera sott’olio era per Nonna una specie di trademark.)

un’oliva nera conservata sott’olio (In frigo, Nonna aveva sempre un barattolo di queste olive spiegazzate. Ne metterebbe una in certi piatti, e.g., la pizza, o la calzone di spinaci e manzo macinato. Io direi di provare altre olive; le kalamata e le grandi olive verdi siciliane sarebbero perfette. Ma dico questo con esitazione, poiché quest’oliva nera sott’olio era per Nonna una specie di trademark.)

* = Addendum (settembre 2016): Il mese scorso esaminai un fascicolo di vecchie ricette ingiallite. Trovai un foglietto di carta su cui avevo annotato la ricetta di mia nonna delle braciole. Avevo completamente dimenticato che io e lei l’avessimo mai discusso. Come c’era da aspettarsi, c’era più dettaglio del fissare delle braciole che c’era della loro cottura! (Lei era sarta!) Per fortuna, in questo post (che scrissi a memoria), ne ricordai tutto, tranne un solo ingrediente: lei aggiungeva un po’ di pangrattato. Certamente un tocco siciliano. Tuttavia, se l’aggiungiate, siate sicuri d’inumidirlo con un po’ di olio, di latte, di acqua … oppure una goccia di vino!

Qua confesserò di aver trovato qualche volta le braciole di Nonna un

pochissimo secche. Ho visto una ricetta che suggeriva di spalmare un po’ di strutto oppure olio d’oliva sopra la carne. Mi è venuta l’idea di fare un impasto. Ho spesso lo strutto casereccio in frigo, ma oggi no. E avevo poco prezzemolo in giardino ma abbastanza timo. Timo essendo un meraviglioso complemento al manzo, ho scelto quello. Dunque, nel robot ho messo olio, timo, pecorino, pepe nero, e ho aggiunto uno spicchio d’aglio. Un tal impasto fa miracoli in molti tipi d’involtino di carne.

Poi, ho fatto un piccolo sbaglio. Ho deciso di aggiungere pure i pistacchi al robot. L’impasto era fantastico e interessantissimo. Ma alla fine, quando mangiavo le braciole finite, non mi potevo affondare i denti nei pistacchi, che facciano un contrasto importante alle uvette dolci.

Allora, come si legano le braciole? Nella memoria mia, Nonna usava solo gli spilli d’acciaio. Comunque, mia mamma dice che prima, Nonna usasse lo spago da cucina. Non so perché cangiò metodo.

Poi, Nonna faceva rosolare le braciole. Nella padella più grande che aveva, metteva olio d’oliva, cipolla affettata, sale e pepe. (Non mettereste aglio se già ci stia nelle braciole.) A turno, lei faceva rosolare in questa padella non solo le braciole, ma tutte le carni che andavano nel sugo. Il grosso pezzo di controfiletto ... il carré delle costole di maiale ... le salsicce se le usasse (ma a volte le metteva crude direttamente nel sugo) ... e le famose polpette ...

Poi, come si diglassa questa padella, con tutti i sapori del Paradiso?

Nonna non metteva mai nè vino nè brodo nel sugo. Lei, per diglassare questa padella, metteva una scatola di 170 gr. di concentrato di pomodoro e due scatolate di acqua (c. 350 mL). Questo sughetto saporito andava nella grande pentola che già conteneva il resto del sugo.

Nonna non metteva mai nè vino nè brodo nel sugo. Lei, per diglassare questa padella, metteva una scatola di 170 gr. di concentrato di pomodoro e due scatolate di acqua (c. 350 mL). Questo sughetto saporito andava nella grande pentola che già conteneva il resto del sugo.

(Una piccola digressione sulle polpette. Mettere l’aglio o non mettere l’aglio? Se mettiate l’aglio crudo, sarebbe troppo forte. Senza nessun aglio, ci manca una piccola qualcosa. Cosa facevano i miei nonni? Quante volte sono stato testimone a questa procedura. Loro conservavano le fette di vecchio pane nel forno freddo. Dopo un paio di giorni diventavano ben rafferme. Nonno prendeva uno spicchio d’aglio nelle sue dita e strusciava l’aglio contro il pane duro. Poi, metteva questo pane aromatico nella grattugia palmare — tipo che si usa oggi per il parmigiano, eccetto che in quei tempi le grattugie fossero di acciaio. Così, faceva il pangrattato casereccio che poi si usava nelle polpette. Figuratevi il profumo!)

(Una piccola digressione sulle polpette. Mettere l’aglio o non mettere l’aglio? Se mettiate l’aglio crudo, sarebbe troppo forte. Senza nessun aglio, ci manca una piccola qualcosa. Cosa facevano i miei nonni? Quante volte sono stato testimone a questa procedura. Loro conservavano le fette di vecchio pane nel forno freddo. Dopo un paio di giorni diventavano ben rafferme. Nonno prendeva uno spicchio d’aglio nelle sue dita e strusciava l’aglio contro il pane duro. Poi, metteva questo pane aromatico nella grattugia palmare — tipo che si usa oggi per il parmigiano, eccetto che in quei tempi le grattugie fossero di acciaio. Così, faceva il pangrattato casereccio che poi si usava nelle polpette. Figuratevi il profumo!)

In totale il sugo di Nonna cuoceva per parecchie ore. Le polpette rosolate ci andavano solo 30 minuti prima della fine. Ciascuna delle altre carni avevano i loro propri tempi di cottura. Le braciole Nonna metteva un’ora prima della fine. (E a proposito, Nonna metteva il basilico solo 5 minuti prima della fine!)

A questo punto, mi devo discostare dalla cucina di Nonna, che non faceva mai le braciole separatamente da un gran sugo.

Voi sicuramente avrete opportunità di fare solo le braciole, senza un sugone. Infatti, le originali braciole ottocentesche erano così, con il loro proprio sughetto.

Voi sicuramente avrete opportunità di fare solo le braciole, senza un sugone. Infatti, le originali braciole ottocentesche erano così, con il loro proprio sughetto.

Dopo di far rosolare le braciole, diglassate la padella. Io ho usato la semplice acqua. Vino rosso sarebbe delizioso, specialmente se usiate Nero d’Avola oppure Lacryma Christi del Vesuvio. Per carità non usare Chianti o un altro vino che si scontra con la cucina meridionale. (Ironicamente, due vini dell’estremo Nord si concordano benissimo con la salsa rossa: l’audace Barbera e il mite Dolcetta d’Alba.)

Se non usiate vino, potreste usare il brodo casereccio di manzo o di maiale. Ma l’acqua funziona benissimo. E le braciole già contengono un assortimento complesso di sapori. Non esitare di usare la semplice acqua, come ho fatto io.

Alla padella diglassata, mettete i pomodori pelati che in anticipo avete già passato nel frullatore. (Non usare nè i pomodori già passati nè il concentrato.) Aggiungete un po’ di sale e pepe, ma non aggiungere mai lo zucchero al sugo. Nonna usava qualche uvetta e un pezzo di carota. Fareste bene aggiungendo un terzo ingrediente: qualche pomodoro secco al sole. (Non li ho mai visti nella cucina di Nonna, ma lei parlava nostalgicamente nei pomodori secchi al sole, che ricoprivano un ruolo importante della cucina di mamma sua. Mica potevano permettersi molta carne! Ecco uno dei vantaggi di aver sposato mio nonno macellaio!)

Fate cucinare lentamente il sughetto per un’ora. Durante la cottura, potete aggiungere un po’ d’acqua quando necessario. Ma non si aggiunge mai il vino o il brodo dopo il diglassare iniziale. Non volete sopraffare il gusto dei pomodori.

Io non ho rimosso mai le braciole dalla padella, perfino durante il diglassare; le ho fatte cucinare una mezz’ora al lato. Per una cottura più corta, potete far rosolare le braciole, rimuoverle dalla padella, diglassare la padella, far cuocere il sughetto per 30 minuti, poi tornarci le braciole e farle cuocere 15 minuti al lato. Il tempo totale di cottura rimane 60 minuti.

Come alcune ricette dei monsù (e.g., l’Agglassato), il sughetto fa un accompagnamento fenomenale alla pasta. Così, potete preparare il primo e il secondo simultaneamente. Ho fatto così io, scegliendo come pasta le campanelle. Secondo me, è la pasta perfetta per questo sughetto; non vi posso dare una ragione logica perché.

Questa ricetta è apparsa precedentemente come parte de Le Ricette delle Nonne.

Labels:

Beef,

Bourbonic recipes,

Cucina napoletana,

Cucina siciliana,

Manzo,

Monsù,

Monzù,

Neapolitan cuisine,

Piatti emblematici,

Ricette borboniche,

Second Courses,

Secondi,

Sicilian cuisine

Buon compleanno, Giacomo Orefice!

| Buon compleanno, GIACOMO OREFICE, compositore ebreo-italiano dell’epoca veristica, nato a Vicenza il 27 agosto 1865, morto a Milano il 22 dicembre 1922. Scrisse opere fra le quali Chopin fu la più famosa. (Si cantò anche in Polonia, in traduzione polacca.) Nell’opera, Orefice si avvalse delle melodie di Chopin. Ma questo non diminisce il fatto che Orefice fu un compositore capacissimo che poté scrivere la bella musica. Ed ecco! Ascolta! La voce di Ferruccio Tagliavini! Chi oggi è degno di sciogliere il legaccio de’ calzari di Tagliavini?! Godete questa voce estasiante, e la voce bellissima di sua moglie, Pia Tassinari. “Sera ineffabile” dal IIº atto di Chopin. San Francisco Opera Orchestra, diretta dal mº Gaetano Merola (registrazione dal vivo, 16 October 1949). | Happy birthday, GIACOMO OREFICE, Jewish-Italian composer of the Verismo era, born in Vicenza 27 August 1865, died in Milan 22 December 1922. He wrote operas, of which Chopin was the most famous. (It was even sung in Poland, in a Polish translation.) In the opera, Orefice avails himself of Chopin's melodies. But this does not diminish the fact that Orefice was a very capable composer who could write beautiful music. And behold! The voice of Ferruccio Tagliavini! Who today is worthy of loosening his sandal straps?! Enjoy this ravishing voice, and the beautiful voice of his wife, Pia Tassinari. "Sera ineffabile" from the second act of the opera Chopin. The San Francisco Opera Orchestra, conducted by Gaetano Merola (live recording, 16 October 1949). |

mercoledì 21 agosto 2013

What is Southern Italy?

| At the Papal-Bourbon frontier. At left, Falvaterra, with the crossed keys and the year the marker was installed. At right, San Giovanni Incarico, with the fleur-de-lys and the number of the marker. Photos: Wikipedia.it |

I discovered that there is no one response.

To say that Lazio does not belong to the South is too simplistic. Historically, many towns in Lazio were part of the South. But on the other hand, to define the South strictly according to the Bourbon borders – i.e., the borders of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies – is too simplistic in another way. It excludes Sardinia. And it excludes Pontecorvo and Benevento, two Papal enclaves. How can you say that Benevento isn't in the South?

Therefore, I decided that my definition of the South will be: all of the land that is south of the northern border of the Two Sicilies, plus Sardinia.

But where is this border?

It's a little complicated. To draw this border, we have to dissect the provinces of Latina, Frosinone, and Rieti.

Let's start on the Mediterranean side. Sperlonga is a coastal town about 15 km west of Gaeta. Bordering Sperlonga on the west is another coastal town, Terracina. Terracina always resisted French domination and remained part of the Papal States. Therefore, we know where to begin our border: between Terracina and Sperlonga.

|

| Sperlonga Photo: Wikipedia.it |

|

| Isola del Liri, the Great Waterfall Photo: Wikipedia.it |

After Carsoli, we leave Abruzzo and re-enter Lazio. Once again, the border becomes complicated, dissecting the province of Rieti. After Tufo Alto (a frazione of Carsoli), the first town we reach is Pescorocchiano. (The three towns in Rieti west of Carsoli – Turania, Collalto Sabino, and Nespolo – were all Papal.) From Pescorocchiano we arrive at Fiamignano, Petrella Salto, Cittaducale, Lugnano, Cantalice, Pian de’ Valli, and Leonessa – all towns in Rieti. (West of Leonessa is Rivodutri, a Papal town.)

| Leonessa Photo: © Simone Telari (Flickr.com) |

At the coast we are at Martinsicuro. North of us is Porto d’Ascoli, a Papal town.

|

| Martinsicuro Photo: Flickr.com |

| Map © Leonardo Ciampa |

Cos'è il Sud Italia?

| Alla frontiera pontificia-borbonica. A sinistra, Falvaterra, con le chiavi decussate e l’anno di apposizione. A destra, San Giovanni Incarico, con il giglio e il numero d’ordine. Foto: Wikipedia.it |

Ho scoperto che non ce n’è una risposta sola.

Dire che il Lazio non appartenga al Sud è troppo simplistico. Storicamente, parecchi comuni laziali facevano parte del Sud. Ma d’altro canto, definire il Sud strettamente secondo i confini borbonici – cioè, i confini del Regno delle Due Sicilie – è troppo simplistico in un altro modo. Esclude la Sardegna. Ed esclude Pontecorvo e Benevento, due enclavi pontifice. Come si può dire che Benevento non sia nel Sud?

Dunque, ho deciso che la mia definizione del Sud sarà: tutta la terra che sta a sud del confine settentrionale delle Due Sicilie, più la Sardegna.

Ma dov’è questo confine?

È un po’ complicato. Per stabilire questo confine, dovremo dissezionare le province di Latina, Frosinone, e Rieti.

Cominciamo al lato mediterraneo. Sperlonga è un comune costiero circa 15 km ovest di Gaeta. Confinando Sperlonga a ovest è un altro comune costiero, Terracina. Terracina sempre resisteva il dominio francese e rimaneva parte dello Stato Pontificio. Dunque, sappiamo dove iniziare il nostro confine: fra Terracina e Sperlonga.

|

| Sperlonga Foto: Wikipedia.it |

|

| Isola del Liri, la Cascata Grande Foto: Wikipedia.it |

Dopo Carsoli, lasciamo l’Abruzzo e rientriamo al Lazio. Di nuovo, il confine diventa complicato, dissezionando la provincia di Rieti. Dopo Tufo Alto (una frazione di Carsoli) il primo comune che raggiungiamo è Pescorocchiano. (I tre comuni reatini a ovest di Carsoli – Turania, Collalto Sabino, e Nespolo – erano tutti pontifici.) Da Pescorocchiano arriviamo a Fiamignano, Petrella Salto, Cittaducale, Lugnano, Cantalice, Pian de’ Valli, poi Leonessa – tutti comuni reatini. (Ovest di Leonessa è Rivodutri, sempre un comune papale.)

| Leonessa Photo: © Simone Telari (Flickr.com) |

Alla costa siamo a Martinsicuro. A nord di noi è Porto d’Ascoli, un comune pontificio.

|

| Martinsicuro Foto: Flickr.com |

| Mappa © Leonardo Ciampa |

martedì 20 agosto 2013

An interview with Rosaria Barbarinaldi

| |

| pitturiamo.it |

(The following is an English translation of the original Italian interview.)

LC: You live and work in Basilicata, but you are of Neapolitan origin, is that right? In what town were you born?

RB: I live and work in Basilicata, and in Basilicata I was born. On November 22, 1971, in Ferrandina, a very beautiful Renaissance town lying on a hill of the Materano*, my very sweet mother brought me into the world. I am not of Neapolitan origin, but to Naples I am very tied. It was in that warm, colorful place that I got my degree in architecture, and it was there that I began my artistic journey. The poems in dialect that I have written are an homage to Naples. For about 9 years I have lived and worked in Episcopia (province of Potenza), a stupendous Medieval hamlet in the middle of the Pollino National Park.

LC: Tell us something about your childhood.

|

|

RB: Mine was a serene childhood. I was a very shy, reserved child, but I was always surrounded by friends. I grew up in the love of a family that was humble but incredibly rich in feelings. I was the third of four children; my father was a blue-collar worker, my mother a housewife. Without question it was my father who transmitted to me my passion for travel and for art. He was an outstanding carver; with a piece of wood he could create anything. Unfortunately he passed away this year, leaving an unfillable void.

LC: That you are an artistic person is a very obvious fact. When did you become aware of your artistic potential? Or is it an awareness that you had from the beginning?

RB: Frankly, I never considered myself an artist. Painting and poetry for me are “attimi di sfogo” (“moments of release”**). They allow me to unleash all of my tensions, my torments, my anger, my love; they are a concentration of all of my emotions. If art is all that, then I am an artist.

LC: Of the three arts in which you are expert — painting, poetry, and architecture — which of the three manifested itself first?

RB: “Expert” is too big a word; it doesn’t represent me. Perhaps it would be better to say “interested.” I have written poetry and painted out of passion since adolescence. Architecture followed later.

LC: Which of the three do you feel most strongly? Are you “more of a painter,” “more of a poet,” or “more of an architect”? Which of the three do you feel that in your soul you truly are?

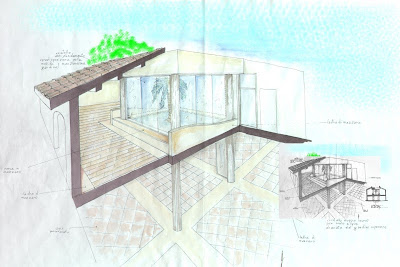

RB: In painting and poetry I don’t have to answer to anyone. Therefore I can give free sfogo to my imagination and my unconditional feelings. Through poetry and painting, I interpret and represent that which is around me from my totally personal point of view. I don’t think I can expend all of this to my work. I work in architecture and internal design. In my work I interpret and try to represent, with my every intervention, the point of view of the client. My motto in architecture is, “La materia prende forma dall’anima di chi dovrà viverla.” (“The material takes its form in the soul of the person who will have to live it.”)

LC: “Materia” in the sense of the physical materials, or “materia” in the sense of the philosophical concept?

RB: By materia I mean the object, the house, the furniture, and the form that they will have to assume or become. Obviously, the form that the materials take should mirror the soul and the desires of the person who will have to use them, therefore live them.

LC: Tell us a little about your current activities.

RB: I think one has already figured out from my previous responses that I occupy myself with architecture for work and for passion, and with painting and poetry for passion only. I have showcased my paintings in Italy and beyond continuously since 2008, with some success. Also in 2008 I decided to publish my poetry on the website Scrivere. I had some success, and I had a means of meeting other people who share this passion of mine, which materialized in the publication, together with other authors, of two books: “San Valentino 2009,” published in 2009, and “Addio Alda,” published in 2010. In 2009 I participated with one of my poems in the compilation of the anthology, “Una poesia per l’Abruzzo.” The proceeds of the book were donated as a benefit to an orphanage in L’Aquila. In 2012 I participated, again with other authors, in the compilation of another anthology, “Poeti di ...Versi (Vol. 2).” In 2013 I published some of my poems, together with other authors, in the book, “Viaggi Di Versi,” which was reviewed by Elio Pecora.

LC: You one said, “La mia idea di architettura è molto simile a quella di un poeta, di un artista, di uno scrittore.” (“My idea of architecture is very similar to that of a poet, of an artist, of a writer.”) Can you give us an example of your approach to an architectural problem that you would confront in a different manner than a “normal architect” who doesn’t have the same artistic sensibilities?

RB: My idea of architecture, like I said earlier, is like that of a poet or artist, the difference being that the artist represents his or her own world from a personal point of view. The architect should represent and interpret the point of view of the customer (within the boundaries of decency). The architect’s skill lies precisely in her ability to understand the taste and the desire of the client who stands before her. This is what renders my participation different from that of someone else. Probably this is what makes me different from my colleagues.

* = The Materano is a regional park in Basilicata. The full name is Parco archeologico storico-naturale delle Chiese rupestri del Materano, but it is also called Parco della Murgia Materana. (L.C.)

** = Sfogo is a wonderful, untranslateable word. It means a venting, a letting off of steam, an outburst or eruption. In this case, naturally, it refers to the release of pent-up creative energy. (L.C.)

| |

| pitturiamo.it |

| |

| Barbarinaldi.com |

|

| Barbarinaldi.com |

|

| Barbarinaldi.com |

Iscriviti a:

Post (Atom)